Coaching is defined as partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximise their personal and [life] potential.

– The International Coach Federation (ICF)

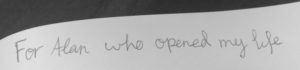

Alan coaches a young client. (Note: there is no speaking audio in this clip).

In a world of speed and efficiency, it’s no surprise that most people resort to shortcuts in small talk. It has been my experience that the most common (and cliché) question is:

So, what do you do?

For many professions, this has a simple answer. Graphic designer, CEO, artificial intelligence researcher, foreign currency trader. These are easy, familiar occupations.

The kind of coaching that I do is so outside of the ordinary that it can be a challenge to explain. Sure, executive coaching is more accessible now than ever before. But coaches specialising in families are extremely rare—less than 1% according to the 2016 report by the International Coach Federation.

Rarer still is a coach specialising in high ability children and their families (I generally work with those children with IQs in the top 10%, and often the top 1%…).

But even with all of this explained, it still doesn’t tell people what it is that I do. Here’s how I wrote about articulating this kind of magic in my third book, Bright:

“…most of the theory is meaningless unless it is used with and applied to children in real life. It’s not possible to graph your child’s ‘passion for counting absolutely everything including nutritional information on food packaging’, or their ‘motivation to learn to read the newspaper at the age of two’. Those things are tangible, words don’t do them justice. Comic book artist and creator of Calvin and Hobbes Bill Watterson puts it like this: ‘That’s the whole problem with science. You’ve got a bunch of empiricists trying to describe things of unimaginable wonder.’ ”.

So, here’s a snapshot of what I do. (Some names have been changed, and sometimes it is a composite of two or more clients.)

Real life stories. Authentic children. Genuine parents. Human families at their best. Lives being changed.

Energetic. Talkative. Physically intelligent…

Background

David* is a bright eight-year-old living in a capital city in Australia. He attends a specialist school. He has not yet been IQ tested. He is charismatic and dynamic. He loves movement and sports (including the young version of Australian Rules Football, Oztag!), and seems to have boundless energy and zest.

David has no learning difficulties or neurodevelopmental disorders. He is an ordinary, extraordinary, bright boy!

After seeing the benefit and outcomes that coaching brings to my other bright clients, David’s mum brought him to Life Architect for coaching.

What we did

Over three months (with twelve sessions), we explored David’s strengths and talents in a playful environment using the Blueprint program. We integrated my version of Lego Serious Play to ask questions and find solutions to questions. We looked at handwriting techniques to help David in the classroom.

“Homework” included Lego models, drawing, and finding longer solutions to more challenging questions.

Outcomes

David’s confidence soared even further, with a new and broader foundation for realising his capacity.

The program allowed his mum to see David in a different light, and to adopt new strategies in parenting, speaking, and listening to him.

His engagement at school increased, and his grades improved.

His mum comments: “Thanks for your great coaching experience. We have really enjoyed our time with you.”.

Sporty. Eloquent. Bored…

Background

Lauren* is a gifted nine-year-old living in a regional part of Australia. She attends a standard school. She has an IQ of around 135; far above the reported IQs (in the 120s) of James Watson (co-discoverer of the structure of DNA), and theoretical physicist Richard Feynman. She is eloquent and knowledgeable. She loves sports, ballet, and maths.

Lauren has no learning difficulties or neurodevelopmental disorders. Perhaps because she is gifted (where things have historically come easily to her), she does have a fear of failure.

After attending one of my seminars, Lauren’s mum got in touch to see how coaching could benefit her daughter.

What we did

Over 1 month (with three sessions), we were able to dive into Lauren’s passions and key strengths. We involved her mum in dialogue, though Lauren would often articulate herself extremely well.

“Homework” included short paragraphs, some drawings, and applying new social skills to use with friends.

Outcomes

Lauren came to understand how her strengths and talents could be applied in both the sporting arena and the rest of the world.

The condensed program was useful here, as she quickly opened up and began answering complex questions with her own deep insights.

Her engagement at home and in her sports increased, and her mum reports that she became more focused and open to “trying new things” with a lessened fear of failure.

Her mum comments: “In hearing your coaching with my daughter, I realised that she can reflect quite extensively on what she is talking [about]… she said more than she would have said normally to me. You drew her out!”.

Charismatic. Well-rounded. Socially isolated…

Background

Nathan* is a gifted fourteen-year-old living in a capital city in Australia. His Full Scale IQ is in line with reported IQs of Bill Gates and Albert Einstein. He is confident, charismatic, and has a long list of hobbies and interests. He was bullied in grade eight, and his parents chose to switch schools from a well-known Grammar school to a more accommodating specialist school, and took him to see a counsellor.

After dealing with the negative parts of this experience through external counselling, and seeing a pathway to provide him with access to the positive parts of himself, his parents approached me for coaching.

What we did

Over three months (with twelve sessions), we explored Nathan’s innate strengths, talents, and growth environment using the Blueprint program.

Both parents (mum and dad) were involved in sessions.

Negative self-talk was replaced with affirming statements.

“Homework” included videos, presentations, designs, journal entries, and a complete life scripting…

We integrated life scripting, where he sat down to “re-architect” his future life—over the next three months to five years—writing his own new story on paper.

Outcomes

For perhaps the first time, his long-winded, meandering thoughts (presented as part of his charismatic style!) were treated with the respect, dignity, and attention that they deserved. This child wasn’t just brilliant—he was a genius!

His focus at school went from zero to excellent, and he set new, high targets for his own school grades.

Towards the end of the coaching program, with his newfound understanding of himself, he applied for and was accepted into a course at a prestigious university in America.

His mum comments: “You’ve had a HUGE impact on him. He is starting off this year fresh, motivated, and with a really positive attitude. He has already planned out his goals and just sees things in a completely different light.”.

Bonus

Here is an extract from a chapter in my third book, Bright.

Triceratops. Stegosaurus. Tyrannosaurus Rex. Diplodocus. Iguanodon.

Even though she was just three years old, Isabelle could pronounce the full names of all the greatest dinosaurs, and knew the differences between them. She knew why an Ichthyosaurus was classed as a reptile, and not a dinosaur. She could also describe the structure of a Gastonia (both her mum and I had to look that one up—it was definitely a dinosaur!).

The school system in England starts slightly earlier than most of the rest of the world. In fact, children can begin “nursery” during the first school term after their third birthday.

So Isabelle began, in England, her introduction to schooling—and to one of the challenges of being bright—at the tender age of three. Surrounded by other children her own age, Isabelle began conversations about dinosaurs with anyone she could. Or at least, she tried to. Her efforts were rewarded with grunting from the other toddlers.

Can you imagine what it feels like to be in a situation where you are completely surrounded by other humans who won’t or can’t communicate with you?

Isabelle’s IQ score sits somewhere between 165 and 171, depending on the type of test. And yet her nursery placed her in the same “bucket” as 30 other toddlers who hadn’t yet learnt to pronounce the word “dinosaur”. (Former American president Thomas Jefferson noted: “There is nothing so unequal as the equal treatment of unequal individuals.”)

So in the middle of this sea of grunting inequality, and still as a three-year-old, Isabelle had just a few options.

Option number one was to remove herself from the environment. Not an easy task as a child. Isabelle tried to escape from the nursery several times.

Option number two was to get the attention of those around her by misbehaving or “acting out”: she could let the world know that she was not flourishing. This choice to misbehave is one of the only outlets that children can see. Of course, this resulted in her spending a lot of time in the naughty chair. With no direct training in working with gifted children, her teachers remained unsympathetic.

So, Isabelle reverted to a fascinating third option; a way of being that many adults revert to as well. She began playing down.

Isabelle went from conversations about animals, birds, and fossils, to something much different. Her mum reports that Isabelle began using baby talk.

Discussions which had previously been about the Jurassic period were replaced with baby language like “mama”. And where once Isabelle had fluent answers to thorny adult questions, her new response was, “I don’t know.”

Her parents were devastated. Within weeks, they had taken advice from a child psychologist, and moved Isabelle into home-schooling. Her behaviour changed back nearly overnight.

Do you know of someone who plays down? Who tries to “blend in” so that they won’t cause a fuss?

The idea of playing down cannot possibly serve a bright child, nor indeed anyone.

The concept of playing down—deliberately handicapping one’s own passion, confidence, walk, presence, choice of friends, talking, and happiness—is terrifying.

Indeed, there is an emotional cost to playing down what we know to be our authentic self. Making the choice to become invisible, or to camouflage our real selves, certainly helps to avoid the issue of social isolation.

But it uncovers an even greater issue. Camouflaging and pretending withholds our greatest self from those around us. Much worse, it can eventually become self-alienation—literally becoming a stranger to our self.

Picture a cheetah slowing down so that the other animals can keep up.

Imagine a peacock choosing to tone down its colours to make the other birds feel more comfortable.

Or a giraffe crouching a little so that he doesn’t stick out so much.

Our children are coming from a place of immensity, an endless well of uniqueness. It takes special guidance to ensure that they continue to bring their power and completeness to every situation; to allow them to be themselves so that they can be themselves.

There’s a happy continuation for Isabelle. By the age of seven, she has found a public school with specialist gifted teachers (the principal has a gifted family of her own). Here, she is treated as “special needs”—because she is! She is given personalised lessons in Latin, high-school chemistry, and specialist subjects (including pharmaceuticals and immunisation in Third World countries). Her current goal is to win a Nobel Prize, making advances in the same fields as Einstein.